Whether you are learning about computer networking through practice labs or are a veteran network administrator, you may have noticed that occasionally, when you test reachability to a specific device with the ping command, the first packet is lost.

1

2

3

4

5

6

Router#ping 192.0.2.10

Type escape sequence to abort.

Sending 5, 100-byte ICMP Echos to 192.0.2.10, timeout is 2 seconds:

.!!!!

Success rate is 80 percent (4/5), round-trip min/avg/max = 1/1/3 ms

There are many scenarios where you may observe this behavior, but it usually occurs when a router along the path between the device you initiate the ping command from and the device you are targeting with the ping command does not have the Media Access Control (MAC) address resolved for an IPv4 address using Address Resolution Protocol (ARP). This IPv4 address could be the IPv4 address targeted by the ping command, or it could be an IPv4 address of an intermediary router that is the next hop in the path to get to the targeted device. Regardless, this is expected behavior commonly seen when the ping command is the first set of traffic sent to a specific destination or through a specific path. Typically, subsequent ping commands do not show any lost packets.

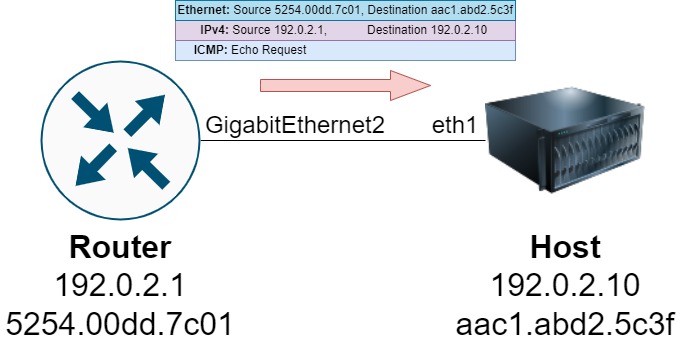

In this article, we will illustrate how and why this behavior happens by focusing on a simple topology where a router is attempting to ping a directly connected host.

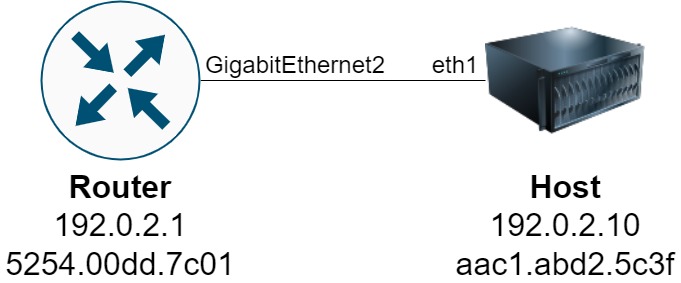

Topology

First, let’s review the topology we will use in this article.

This topology involves two devices - a Catalyst 8000v virtual router named “Router” running IOS-XE 17.08.01a, and a Linux host named “Host” running the Ubuntu 20.04 operating system. Router’s GigabitEthernet2 interface with an IP address of 192.0.2.1/24 is directly connected to Host’s eth1 interface with an IP address of 192.0.2.10/24.

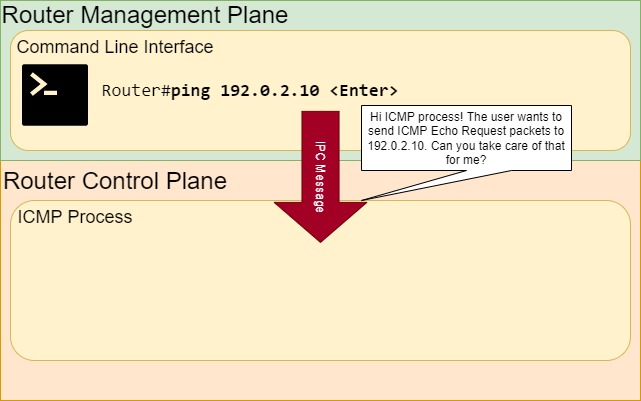

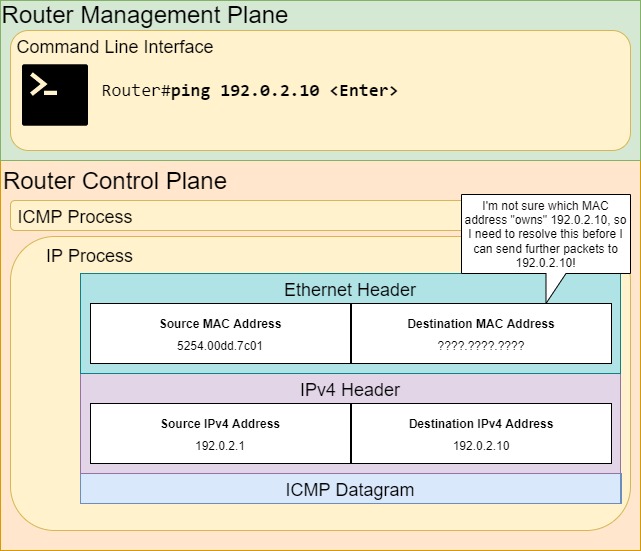

Executing the First Ping

Let’s walk through precisely what happens when the ping 192.0.2.10 command is executed. First, the management plane sends a message through InterProcess Communication (IPC) to a software process of the network operating system responsible for handling the Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) for the device. We will refer to this software process as the “ICMP Process”. This IPC message informs the ICMP-related sofware process that the user would like to send ICMP Echo Request packets to a specific IPv4 address.

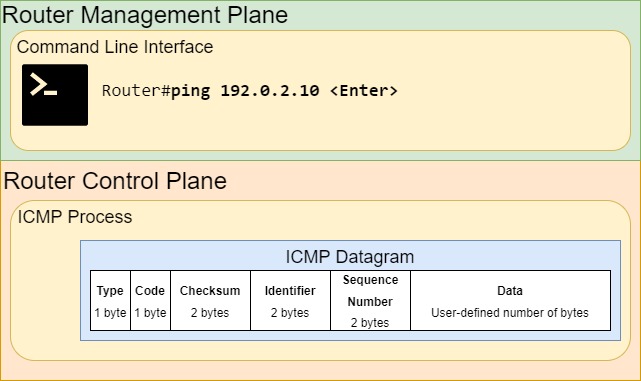

The ICMP-related software process will internally craft an ICMP Echo Request header with a starting sequence number. In Cisco IOS-XE, this is typically a sequence number of 0.

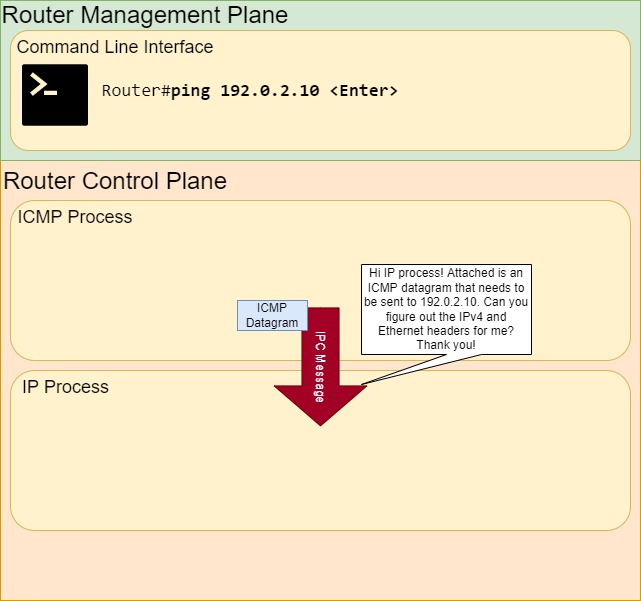

This data is typically passed to another software process via an IPC message responsible for crafting IPv4 and Ethernet headers for the packet. We will refer to this software process as the “IP Process”.

While crafting the IPv4 and Ethernet headers, the router references its routing table for the destination IP address 192.0.2.10. In our scenario, the longest prefix match for this IP address is the 192.0.2.0/24 route directly connected to interface GigabitEthernet2.

1

2

3

4

5

6

Router#show ip route 192.0.2.10

Routing entry for 192.0.2.0/24

Known via "connected", distance 0, metric 0 (connected, via interface)

Routing Descriptor Blocks:

* directly connected, via GigabitEthernet2

Route metric is 0, traffic share count is 1

Based on this information, the router knows the following facts:

- This ICMP Echo Request packet needs to leave the router out of the router’s GigabitEthernet2 interface.

- The source IPv4 address of the packet will be the 192.0.2.1 address assigned to GigabitEthernet2.

- The destination IPv4 address will be the 192.0.2.10 targeted by the

pingcommand. - The source MAC address in the Ethernet header will be 5254.00dd.7c01, which is the MAC address assigned to the GigabitEthernet2 interface. This is shown below through the output of the

show interface GigabitEthernet2command.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Router#show interface GigabitEthernet2

<snip>

GigabitEthernet2 is up, line protocol is up

Hardware is vNIC, address is 5254.00dd.7c01 (bia 5254.00dd.7c01) <<<

Internet address is 192.0.2.1/24

MTU 1500 bytes, BW 1000000 Kbit/sec, DLY 10 usec,

reliability 255/255, txload 1/255, rxload 1/255

Encapsulation ARPA, loopback not set

Keepalive set (10 sec)

Full Duplex, 1000Mbps, link type is auto, media type is Virtual

output flow-control is unsupported, input flow-control is unsupported

ARP type: ARPA, ARP Timeout 04:00:00

Last input 00:21:19, output 00:21:19, output hang never

Last clearing of "show interface" counters never

Input queue: 0/375/0/0 (size/max/drops/flushes); Total output drops: 0

The one fact that the router is currently missing is the destination MAC address of the Ethernet header. This MAC address must be the MAC address assigned to the host’s eth1 network interface, which is aac1.abd2.5c3f as shown through the output of the ip link show eth1 command.

1

2

3

root@Host:/# ip link show eth1

66: eth1@if67: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 9500 qdisc noqueue state UP mode DEFAULT group default

link/ether aa:c1:ab:d2:5c:3f brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 1

To summarize, the router knows the host’s IP address, but does not know the host’s MAC address. The router needs to resolve the host’s MAC address using the host’s IP address.

The router will do this using the Address Resolution Protocol (ARP). The router will consult its ARP cache, looking for an existing entry for 192.0.2.10. The output of the show ip arp 192.0.2.10 command below is empty, suggesting that no such entry exists. This is confirmed with the full output of the show ip arp command.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Router#show ip arp 192.0.2.10

Router#

Router#show ip arp

Protocol Address Age (min) Hardware Addr Type Interface

Internet 10.0.0.2 31 5255.0a00.0002 ARPA GigabitEthernet1

Internet 10.0.0.15 - 5254.0023.d400 ARPA GigabitEthernet1

Internet 192.0.2.1 - 5254.00dd.7c01 ARPA GigabitEthernet2

The router cannot proceed with sending this ICMP Echo Request packet without first resolving the MAC address associated with the host assigned 192.0.2.10. Therefore, the IP Process will erase the ICMP packet from memory.

Note: The reasoning behind why this ICMP Echo Request packet is erased from memory is explained in the “Why Is The First Packet Dropped?” section of this article.

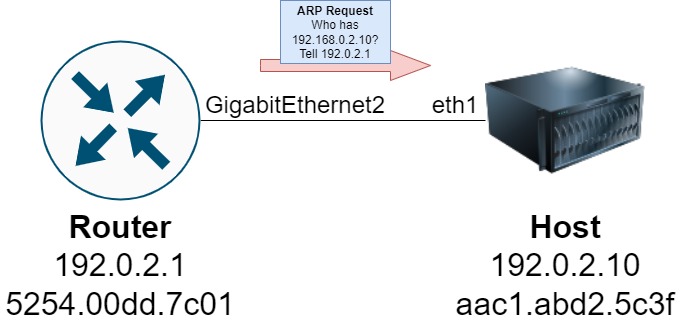

To populate the ARP cache with a valid entry, the router will broadcast an ARP Request frame to all hosts on the 192.0.2.0/24 subnet asking for the host assigned the 192.0.2.10 IP address to respond with the host’s MAC address.

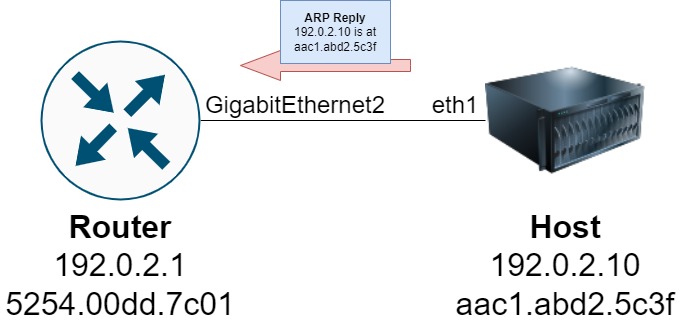

The host will respond with a unicast ARP Reply frame informing the router that the host’s MAC address is aac1.abd2.5c3f.

This procedure is demonstrated through the packet capture on the host below.

1

2

3

4

root@Host:/# tcpdump -i eth1 -vvvv

tcpdump: listening on eth1, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), capture size 262144 bytes

16:53:52.913600 ARP, Ethernet (len 6), IPv4 (len 4), Request who-has 192.0.2.10 tell 192.0.2.1, length 46

16:53:52.913617 ARP, Ethernet (len 6), IPv4 (len 4), Reply 192.0.2.10 is-at aa:c1:ab:d2:5c:3f (oui Unknown), length 28

The router’s ARP cache will now have an entry for 192.0.2.10, as demonstrated through the output of show ip arp 192.0.2.10 below.

1

2

3

Router#show ip arp 192.0.2.10

Protocol Address Age (min) Hardware Addr Type Interface

Internet 192.0.2.10 1 aac1.abd2.5c3f ARPA GigabitEthernet2

Recall that the original ICMP Echo Request packet was erased from memory by the IP Process. The ICMP Process has no knowledge of whether the ICMP packet it crafted and sent to the IP Processs was successfully sent out of the router by the IP Process, or if the ICMP packet was deleted in memory. The ICMP Process simply expects to receive an ICMP Echo Reply packet in response to the ICMP Echo Request packet it created within the defined timeout period (default 2 seconds in Cisco IOS-XE). When this timeout period expires, the ICMP Process will mark that instance of the ping unsuccessful.

At this brief moment in time, the command line output for the ping 192.0.2.10 command will look like the following.

1

2

3

4

Router#ping 192.0.2.10

Type escape sequence to abort.

Sending 5, 100-byte ICMP Echos to 192.0.2.10, timeout is 2 seconds:

.

Executing the Second Ping

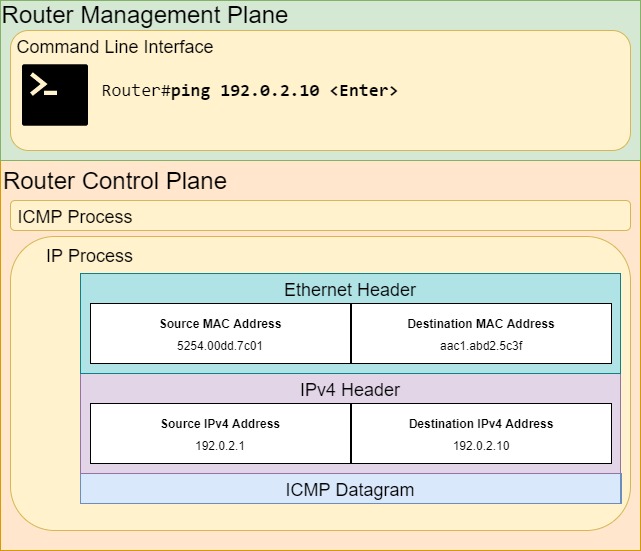

The ICMP Process will repeat the above process when the timeout period for the first ICMP Echo Request packet expires. It will craft the header for an ICMP Echo Request packet and increment the sequence number within the header. For Cisco IOS-XE, the sequence number will be 1. Just like for the previous ICMP packet, this ICMP packet is passed to the IP Process via an IPC message so the IP Process can craft the IPv4 and Ethernet headers.

Now that the ARP table contains an entry for 192.0.2.10, the IP Process can craft accurate IPv4 and Ethernet headers for the ICMP Echo Request packet.

The IP Process will hand this completed ICMP Echo Request packet off to the data plane for transmission on the wire towards the host.

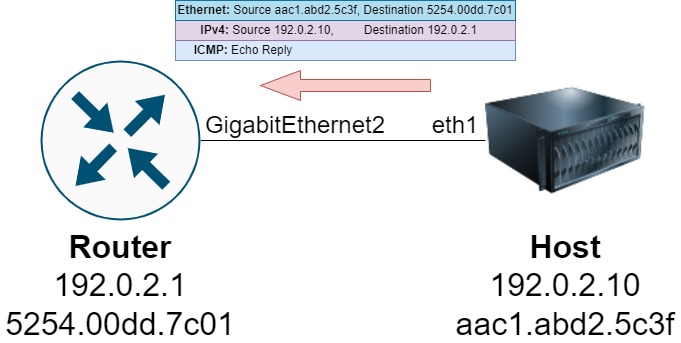

The host will receive this ICMP Echo Request packet and respond with an ICMP Echo Reply packet.

The data plane of the router will receive this ICMP Echo Reply packet, recognize that the packet is destined for the router itself, and send the packet to the control plane (this action is commonly called a punt). The control plane will route this packet to the ICMP Process. The ICMP Process will report that there is bidirectional connectivity with 192.0.2.10. At this brief moment in time, the command line output for the ping 192.0.2.10 command will look like the following.

1

2

3

4

Router#ping 192.0.2.10

Type escape sequence to abort.

Sending 5, 100-byte ICMP Echos to 192.0.2.10, timeout is 2 seconds:

.!

This procedure will repeat three more times, with ICMP Echo Request packets being crafted and transmitted by the router and ICMP Echo Reply packets sent in response by the host. At the conclusion of this transaction, the command line output for the ping 192.0.2.10 command will look similar to the following.

1

2

3

4

5

6

Router#ping 192.0.2.10

Type escape sequence to abort.

Sending 5, 100-byte ICMP Echos to 192.0.2.10, timeout is 2 seconds:

.!!!!

Success rate is 80 percent (4/5), round-trip min/avg/max = 1/1/3 ms

Why Is The First Packet Dropped?

A common question network operators may ask is, “Why is the first packet erased from system memory? Why not buffer the packet in system memory, wait until ARP is resolved for the destination IPv4 address, then transmit it as normal?”

There are two valid explanations for this behavior - conservation of system memory, and an assumption that networks should be lossless.

Conservation of System Memory

Historically, network devices had a relatively small amount of system memory to work with. For this reason, network operating systems tried to utilize system memory as efficiently as possible and protect system memory from unnecessary utilization. This philosophy ensures that network devices can reliably transport data between hosts as fast as possible.

The example in this article utilizes ICMP packets that are 114 bytes long on the wire:

- 80 bytes for the ICMP Echo Request/Reply payload

- 20 bytes for the IPv4 header

- 14 bytes for the Ethernet header

This means the network device would need to allocate a minimum of 114 bytes of system memory (potentially more, if metadata about the packet needs to be stored) to buffer the ICMP packet while ARP resolves. This packet would need to be buffered in system memory for the ICMP timeout period (default 2 seconds on Cisco IOS-XE) while the router tries to resolve ARP for the destination.

There are three problems with this:

- 2 seconds is an eternity to a computer. Humans act on a scale of seconds, while modern computer operations tend to operate on a scale of microseconds, sometimes even nanoseconds. Modern network devices can transport hundreds of thousands of packets during the 2-second timespan it may need to buffer this packet, and some of those packets may need to utilize that system memory.

- Buffered packets can be an arbitrary size. The packet being buffered could be any packet (ICMP, TCP, or UDP) of any length (up to 1514 bytes by default, or upwards of 9000 bytes [or more] if jumbo frames are enabled). The amount of system memory allocated to buffer a single packet must match the size of the packet.

- Multiple packets may be buffered in a short period of time. The network device may not need to just buffer a single packet - there may be multiple packets received for the same destination, or multiple packets received for multiple different destinations, that all need to be buffered in system memory.

As you can imagine, buffering an arbitrary number of packets of an arbitrary size in system memory for a prolonged amount of time is not a scalable option. Several megabytes of the network device’s system memory may be constantly used to buffer packets that may never be transmitted out of the network device. This behavior does not align with the philosophy that network operating systems should utilize system memory as efficiently as possible, so network operating systems choose to erase these packets from system memory as quickly as possible instead of buffering them.

Networks are not Lossless

The protocols that modern computer networks are built upon were originally designed during the height of the Cold War. At the time, the goal was to ensure geographically disparate computers could reliably communicate over unreliable mediums, such as phone lines damaged from warfare, spotty satellite connections, or erratic radio transmissions.

If we fast forward to modern times, the threat of nuclear warfare has subsided, but the unreliable nature of our transmission medium has not. Damaged copper and fiber-optic cables can malform traffic, and the periodic oversubscription of network devices (especially over the Internet) means that networks are lossy in nature. Applications cannot assume that the network is available 24/7/365 and will deliver every single piece of data without loss; however, applications can assume that the underlying protocols computer networking is built on will eventually deliver data as requested.

For this reason, a router dropping a packet instead of buffering it while the router resolves ARP for a destination is a minor inconvenience in the grand scheme of things. In a worst case scenario, this behavior delays connectivity to a destination by a few tenths of a second, with all subsequent connectivity working as expected at normal speeds.

Conclusion

In summary, it is expected behavior for most network operating systems to drop the first ICMP packet sent through the ping command if a router does not have the MAC address for the destination resolved through ARP. If you re-run the ping command immediately after seeing this behavior, you will most likely not see this behavior. This behavior is typically only observed when you are sending traffic to an IP address for the first time (such as if a new host has been recently connected to the network).

It is worth noting that not all network operating systems exhibit this behavior with ping commands. This behavior has been seen on the following network operating systems:

- Cisco IOS

- Cisco IOS-XE

- Cisco NX-OS

This behavior has not been seen on the following network operating systems:

- Juniper Junos OS

- MikroTik RouterOS